Ten years ago, Edward Snowden leaked thousands of classified documents and revealed the extent of surveillance by US intelligence services.

Among many other serious consequences, the Snowden revelations triggered a series of European court cases that invalidated two international agreements—and seriously undermined the ability of US tech firms to operate in the EU.

The Snowden Story

Snowden worked for the CIA between 2006 and 2009, including in a post maintaining network security under diplomatic cover in Geneva. In 2009, he took on a job as an NSA contractor with Dell at the NSA’s offices in a Japanese US airbase.

Dell relocated Snowden to Hawaii in 2012, where he worked in the recently-opened Hawaii Cryptologic Center.

Source: https://web.archive.org/web/20150918033924/https://www.nsa.gov/public_info/press_room/2012/a4_hawaii_final.shtml

Snowden has described his growing disillusionment with US foreign policy while working for the intelligence services, where he learned of practices such as blackmail, assassination, and—most notably—mass surveillance.

In one of many examples, Snowden learned that the NSA was tracking the pornography-viewing habits of suspected jihadists—with the intention to publicise the information and cause the “degradation or loss of (their) authority.”

Source: https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/nsa-porn-muslims_n_4346128#slide=3074349

Snowden also observed how the NSA routinely shared private data with authorities in Israel and other states.

Such information allegedly included transcripts of phone calls between Palestinian Americans and their relatives in Palestine, which could later be used by the Israeli military to target suspected insurgents.

Snowden claimed that despite a legal obligation to minimise any intrusion on US residents’ privacy, the NSA made little or no effort to disguise people’s identities when sharing data with foreign governments.

2013 Snowden Leaks

Snowden claimed he “had access to everything” while working in Hawaii. He also felt that the NSA had not anticipated that a rogue agent could blow the whistle on the agency’s practices.

After taking a job with another NSA contractor, digital consultancy Booz Allen, Snowden’s access levels—and disillusionment—increased further still.

At Booz Allen, Snowden learned of an NSA project known as “MonsterMind” that would detect malware targeting US infrastructure—and which, he believed, could automatically retaliate against the sender.

For Snowden, the automated nature of this process represented a considerable risk, as cyberattacks are often routed through innocent third countries.

After learning of MonsterMind and other NSA projects, Snowden felt the world needed to know the extent of US surveillance practices. He downloaded thousands of classified documents onto portable storage devices and flew to Hong Kong to leak them to journalists.

What Did Snowden Reveal?

The Snowden leaks revealed secret surveillance programmes operated by intelligence services such as the NSA and its UK counterpart, Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ).

Snowden also showed how US national security laws were being applied in practice. From the European perspective, the main relevant US laws include the following:

- Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (“FISA 702”): The primary law covering how intelligence services gather foreign intelligence data on US soil.

- Executive Order 12333 (“EO 12333”), which strengthened the surveillance powers of intelligence services—including with regard to foreign surveillance. The order has been amended several times by various US presidents.

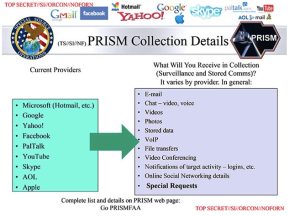

For non-Americans, Snowden’s two most important disclosures related to the NSA’s “PRISM” and “Upstream”, surveillance programmes.

PRISM

The PRISM programme involves the collection of data stored by private companies, including:

- Meta (then “Facebook)

- Microsoft

- Yahoo

- Apple

- AOL

The PRISM revelations also shed light on how US intelligence services interpreted their legal powers. The evidence suggested that safeguards against excessive surveillance were weak, underused, and sometimes ignored.

Upstream

The Upstream programme involves the direct collection of data “in transit” with the cooperation of telecommunications companies.

Data collected via Upstream is intercepted as it passes through fiber optic cables. In one of Snowden’s leaked slides, the NSA referred to a “unique aspect” of Upstream as being “access to a massive amount of data.”

Snowden and the Schrems Cases

In 2013, after learning of the intrusive nature of US surveillance activities, Austrian privacy activist Max Schrems launched a legal challenge against Facebook (and, initially, Apple).

Schrems argued that, by transferring his personal data from its Irish subsidiary to its US parent company, Facebook was putting him at risk of surveillance via the PRISM programme.

Schrems’ case was rejected by the Irish Data Protection Commission (DPC).

“There is an agreement at European level that there’s free movement of personal data between the EU and the US,” said then-Commissioner Billy Hawkes in response to Schrems’ complaint.

Hawkes referred to the EU-US “Safe Harbor Privacy Principles”, a certification scheme adopted as an “adequacy decision” by the European Commission in 2000.

EU data protection law normally requires organisations to implement controls before transferring personal data outside of the European Economic Area (EEA). But such transfers are considered lawful by default if covered by an adequacy decision such as Safe Harbor.

US businesses self-certifying under Safe Harbor were contractually obliged to protect imported EU personal data to a high standard. But Schrems argued that a contractual agreement did not prevent the US intelligence services from accessing his personal data.

However, the Irish DPC felt it could not address the Safe Harbor decision and rejected Schrems’ arguments.

“I am bound by that decision and that is why there is nothing to investigate by me in this case,” Commissioner Hawkes said.

Snowden and the Irish High Court

Schrems appealed the Irish DPC’s decision to the Irish High Court. The opening paragraphs of the High Court’s 2013 judgment described the Snowden revelations as the “backdrop” of the case.

“While it is true that the Snowden disclosures caused—and are still causing—a sensation, only the naïve or the credulous could really have been greatly surprised,” the judge stated.

But while the Snowden leaks might not have revealed much about the nature of US surveillance, the Irish High Court found that Snowden had shed light on the extent of such practices.

“…the Snowden revelations demonstrate a massive overreach on the part of the security authorities, with an almost studied indifference to the privacy interests of ordinary citizens. Their data protection rights have been seriously compromised by mass and largely unsupervised surveillance programmes…

“I will therefore proceed on the basis that personal data transferred by companies such as Facebook Ireland to its parent company in the United States is thereafter capable of being accessed by the NSA in the course of a mass and indiscriminate surveillance of such data.”

As such, the Irish court found that the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) should review the Safe Harbor decision to ensure that it did not violate the fundamental rights of people in the EU.

Snowden and the CJEU

In the decision now known as “Schrems I”, the CJEU also referenced the Snowden revelations.

The court cited Snowden as one of Schrems’ motivations for bringing the case and referenced the Irish High Court’s position that Snowden had revealed the “significant overreach” of the NSA.

The CJEU made two main findings in Schrems I.

First, it addressed the Irish DPC’s assertion that national data protection authorities (DPAs) have no power to assess adequacy decisions adopted by the European Commission (in this case, “Safe Harbor”).

The CJEU disagreed, stating that DPAs were entitled to address any complaint by an individual who felt their rights had been violated by an adequacy decision.

Second, the CJEU took on the task of assessing Safe Harbor itself. The court agreed with Schrems that the decision did not effectively protect the personal data imported from the EU by US companies.

As such, the CJEU tore up a 16-year-old international agreement between the EU and the US that had been used to facilitate billions of data transfers.

The decision caused thousands of companies to turn to other legal mechanisms in order to continue their transatlantic business operations.

Schrems II

Following the Schrems I judgment, Brussels and Washington negotiated a successor to Safe Harbor known as “Privacy Shield.” Schrems challenged Privacy Shield on similar grounds to Safe Harbor.

In the landmark “Schrems II” case that followed, the CJEU found Privacy Shield inadequate for many of the same reasons as its predecessor.

The court held that the framework enabled US intelligence services to indiscriminately surveil people in the EU. And if a European’s data was accessed by the NSA, America’s weak legal protections left the individual with no meaningful way to challenge any violation of their rights.

Furthermore, the CJEU found similar issues with other legal mechanisms designed to facilitate international data transfers, such as the “standard contractual clauses” (SCCs) that can be inserted into agreements between EU data exporters and non-EU importers.

The court noted that laws such as FISA 702 and EO 12333 grant US intelligence services broad powers to conduct surveillance on non-Americans—and a US company’s contractual obligation to keep EU data secure does not affect these powers.

The Post-Schrems II Data Protection Landscape

With Privacy Shield invalidated and SCCs inadequate for most transfers, US companies have struggled to find lawful ways to continue operations in the EU.

But perhaps unsurprisingly, data transfers to the US have largely continued—even where they are likely illegal.

Recommendations from the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) suggest that most data transfers from the EU to the US are unlawful following Schrems II—even where it is highly unlikely that intelligence services would attempt to access exported data.

But besides this non-binding guidance, DPAs have taken a piecemeal enforcement approach, addressing data transfers across scores of individual investigations into the use of tools like Google Analytics and the Meta Pixel—but not banning such products outright.

However, the Schrems II decision finally hit Meta in May 2023, when the Irish DPC reluctantly imposed a €1.2 billion fine on the company—and ordered Meta to stop transferring EEA Facebook users’ data to the US within five months.

The DPC also directed Meta to stop unlawfully storing Facebook data in the US—an order that, if followed, could result in the permanent deletion of every EEA-based Facebook user’s posts, photos, messages, and account data before the end of the year.

Ten Years On from the Snowden Leaks

After blowing the whistle on the NSA in 2013, Snowden fled to Russia, where he was granted citizenship in 2022.

Snowden’s decision to seek sanctuary in Moscow has been controversial. Some otherwise sympathetic commentators have criticised Snowden’s alleged lack of vocal opposition to Putin’s policies, including regarding the invasion of Ukraine.

In a Guardian interview in early June, Snowden said he had “no regrets” about his whistleblowing but that technical advancements in the past decade made 2013 surveillance methods look like “child’s play.”

After Snowden revealed US tech firms’ cosy relationship with the intelligence services, many companies rushed to adopt new privacy measures such as end-to-end encryption.

But these technical measures have not prevented big tech from being caught in the middle of the ensuing decade-long privacy dispute between the EU and the US.

Following the invalidation of Safe Harbor and Privacy Shield, a new data transfer scheme, the “EU-US Data Privacy Framework” (EU-US DPF), should soon be in place—and could save Meta from the Irish DPC’s orders to stop its US data transfers.

But the draft EU-US DPF decision has been criticised by the EDPB and the European Parliament, with both bodies expressing continued concern that the framework will violate EU data protection and privacy rights.

The EU’s digital market remains saturated with US tech firms. European public bodies, businesses, and individuals in the EU use US digital products every day—largely oblivious to the fact that using such products likely violates EU law.

Nowadays, Edward Snowden is seldom mentioned in the context of EU-US data transfers. But his revelations led to a decade of uncertainty around how US companies can continue operating in the EU.

Max Schrems has made clear his intention to challenge the EU-US DPF on similar grounds as its predecessors, Safe Harbor and Privacy Shield.

As such, Snowden’s leaks might continue to disrupt transatlantic data transfers for many years to come.

If you’re curious about how your organization stacks up against industry benchmarks for privacy, test your company’s privacy practices, CLICK HERE to receive your instant privacy score now!